Rejecting “Bullying Panic” (Series on Preventing Student Bullying)

— Don’t Label Every Student Dispute as Bullying

“People’s Daily+” Client, 2025-10-17 11:21

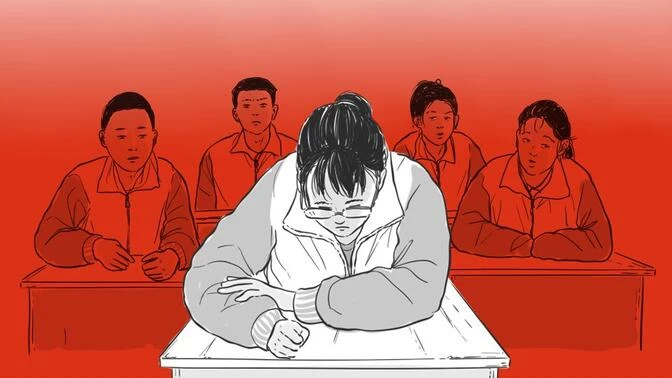

In recent years, as multiple severe student bullying incidents have been exposed in the media, student bullying has gradually become a hot topic of public discussion. Driven by public opinion, an atmosphere of nationwide attention and全社会 anti-bullying is forming. However, on the other hand, the phenomenon of overgeneralization and misuse of the concept of “student bullying” is becoming increasingly prominent. Everything from minor play-fighting and disputes among students to occasional conflicts and even serious violent crimes are being labeled as “bullying.” This situation not only blurs the public’s understanding of the essence of bullying but may also lead to the neglect of victims who truly need help, and even trigger a waste of educational resources and a crisis of social trust.

I. Beware of Conceptual Overgeneralization: When Bullying Becomes an Overused “Label”

On the playground of a key secondary school in a certain city, two eighth-grade boys jostled each other while fighting for a basketball, one of them suffering a scraped elbow. This was merely an accidental incident between students, but the parent of the injured student was unyielding, insisting it be classified as “school bullying,” and posted a video online “seeking help,” which angered the other student’s parent. Ultimately, a normal conflict that could have been resolved through school mediation had to be investigated and handled by the local education bureau.

This phenomenon of misusing the “bullying label” is spreading. One school set up a dedicated bullying report hotline, yet over the course of a year, more than 70% of the reported “bullying incidents” turned out to be ordinary disputes caused by poor communication. The experience of Teacher Li Min (a pseudonym) is even more typical — her class records for the year showed that 53 “bullying complaints” were handled, but only 2 of them met the three defining elements of bullying — malicious attack, power imbalance, and physical/psychological harm. The rest were mostly ordinary conflicts among children.

When accidental pushes on the playground, arguments over stationery, etc., are branded as “bullying,” when teachers are busy handling false reports, when parents overreact due to bullying panic, and when limited educational resources are consumed mediating “false bullying,” the real victims of bullying might be forgotten amidst the noise…

In fact, UNESCO has long cautioned: “Labeling ordinary conflict as bullying may undermine public trust in anti-bullying actions and dilute resources for real victims.” This means that to firmly combat bullying and focus efforts on protecting those who truly cannot protect themselves, it is precisely necessary for society to return to a rational understanding of the bullying concept. Otherwise, the misuse of the bullying concept will blur our measurement of good and evil. Therefore, to clarify the concept and avoid misuse, we must first return to the source and the essential definition of bullying.

II. Returning to the Source: Regaining a Rational Understanding of Student Bullying

Let’s return to the earliest international conceptual definition of school bullying — “A student is being bullied when he or she is exposed, repeatedly and over time, to negative actions on the part of one or more other students, and he or she has difficulty defending himself or herself.” The so-called “negative actions” refer to behavior intended to inflict injury or discomfort upon another. This definition of school bullying was provided in 1983 by Professor Dan Olweus of Norway, the “founding father of school bullying research.” School bullying was thus established as a specific type of aggressive behavior occurring among students. The three characteristics emphasized in this definition — intentional aggression, repetition, and a power imbalance between the perpetrator(s) and the victim — became key criteria for identifying bullying in practice.

Forty years later, in 2023, UNESCO’s chief bullying research expert Professor etc. initiated a redefinition of the school bullying concept. While continuing to emphasize the characteristics of intentional harm and power imbalance, it further stressed that bullying is “unwanted aggressive behavior” that “can cause physical, social, or emotional harm to the target individual or group and the wider school community,” thus emphasizing the “harmful consequences.” It is evident that intentional aggression, power imbalance, and causing harm are the defining features of bullying, which is an international consensus.

When defining the concept of student bullying, China fully drew on these international consensuses and provided a clear explanation based on the local context. The first official document to clearly define bullying was the “Comprehensive Management Plan for Bullying in Primary and Secondary Schools” issued in 2017 by the Ministry of Education and 11 other departments. The document states, “Bullying in primary and secondary schools refers to an incident that occurs on or off campus (including primary schools, secondary schools, and secondary vocational schools), between students, where one party (individual or group) single or multiple times intentionally or maliciously through physical, verbal, or online means implements bullying or humiliation, causing the other party (individual or group) physical injury, property damage, or mental harm, etc.” Subsequently, the “Minor Protection Law” further defined “student bullying” at the national legal level, stating that “student bullying refers to behavior occurring between students, where one party intentionally or maliciously through physical, verbal, or online and other means implements oppression or humiliation, causing the other party personal injury, property damage, or mental harm.” The bullying identification standards in the “Regulations on the Protection of Minors in Schools” issued by the Ministry of Education in 2021 emphasized that bullying behavior is inflicted by one party who holds an advantage in aspects like age, physical strength, or numbers upon the other party. Synthesizing these three definitions, we can outline four key elements for identifying student bullying:

- Subject Element: Both parties are students, and there is a clear power imbalance between the bully and the victim, characterized by the strong oppressing the weak.

- Subjective Element: The bully subjectively has the intent or malice to cause harm to others, i.e., possesses a clear aggressive purpose and motive.

- Behavioral Element: Specific acts of bullying, such as oppression or humiliation, were carried out through physical, verbal, or online means.

- Consequence Element: The victim experiences physical or psychological pain, or suffers property loss, etc.

In short, student bullying can be summarized as “between students, power imbalance, malicious attack (oppression/humiliation), causing harm.” This framework not only distinguishes bullying from other general aggressive behaviors but also provides a clear standard for judging whether an event constitutes bullying.

- Between students means that both the perpetrator and the target of bullying are students enrolled in a school. This distinguishes bullying from aggressive acts occurring between teachers and students, or between external youth and students.

- Power imbalance refers to the inequality between the bully and the victim in terms of physical strength, social status, peer relationships, etc., such as the older bullying the younger, many bullying the few, or the strong bullying the weak. This power imbalance makes it typically difficult for the victim to resist, and the bullying relationship formed is stable and often irreversible. It is this defining characteristic that distinguishes bullying from general aggressive behavior, mutual fights, or other violent acts. Therefore, not all school violence or personal injury at school constitutes bullying.

- As for malicious attack, it means that bullying is an intentional, deliberately harmful aggressive behavior by the perpetrator. This distinguishes bullying from playful roughhousing or conflicts among peers. For instance, the case mentioned at the beginning involved two students arguing over a ball, leading to a fight where one got hurt. While this incident did cause harm to one party, the behavior was not a malicious attack based on a power imbalance; it was a peer conflict during normal sports activity. If we “demonize” such normal frictions in school life, misclassifying ordinary student conflicts or accidental clashes as “student bullying,” and severely punish the involved students, it may trigger a “chilling effect,” causing students to feel apprehensive and afraid to engage in casual play or banter. On the other hand, teachers’ limited attention resources are occupied by “false bullying.” For example, a homeroom teacher might be constantly busy handling various “bullying incidents” like the “eraser dispute,” while failing to notice extortion happening in the school restroom.

- Of course, in practice, we must also be wary of another form of bullying concept misuse — categorizing serious violent crimes (e.g., assault with a weapon) as bullying. Qualifying violent crimes that necessitate judicial intervention as student bullying is not protecting minors; it is potentially “cultivating” juvenile offenders.

Clarifying the scientific definition of student bullying is a prerequisite for accurate identification and effective intervention. However, even with a clear conceptual framework, identifying bullying is not easy, and managing it is even harder.

III. Facing Reality: Bullying Prevention is a Global Challenge

In 1973, the world’s first research monograph on school bullying was published. In 1983, Norway launched the world’s first large-scale intervention against school bullying. To date, global research on student bullying has spanned half a century, and the治理 of student bullying has a history of over 40 years. Yet, so far, no country from Northern Europe to East Asia has claimed to have eradicated the problem of student bullying. Among the hundreds of research reports on school bullying worldwide, not a single one reports a zero bullying prevalence rate. A 2017 UNESCO report indicated that globally, 32% of students are bullied at least once per month on average. Thus, regardless of national borders, geography, culture, or political system, student bullying is a widespread social phenomenon. The World Health Organization, recognizing the universality and harm of student bullying, has identified it as a “global public health problem.” The founder of the Norwegian Centre for Learning Environment and Behavioral Research in Education (related to bullying research) once said, “Acknowledging the widespread nature of the student bullying problem and rationally viewing the long-term nature of bullying prevention work is the foundation for effective and sustainable bullying management.” This was his conclusion after reviewing Norway’s three nationwide student bullying治理 campaigns last century. For us, who only first defined student bullying in a national policy document in 2017, this is a very important reminder.

Accurately understanding the concept of bullying and avoiding its overgeneralization or misuse is the premise and foundation for effectively carrying out student bullying prevention work. When conflicts and disputes arise among students, the first step is to conduct an objective, rational analysis and address it seriously and prudently, replacing panic and blame with wise collaboration. Only in this way can the legitimate rights and interests of real victims be protected, can the unnecessary waste of relevant resources be prevented, and ultimately, can the healthy growth of students be promoted and a harmonious and orderly campus environment be achieved. (Zhang Qian, International Research Center on School Bullying, Capital Normal University)

Editor: Chen Qi

评论(0)

暂无评论